Weekend reading with this 1989 publication.

Peter Holm

AUDRA WOLOWIEC

AUDRA WOLOWIEC

breathing room

plastic bags, thread, wood, tape, air

dimensions vary

2012

site specific installation using natural airflow into and out of a room. attention is placed on one’s own breath as the architecture itself begins to breathe.

PARIS

What’s on show at RAYGUN in Toowoomba and beyond for 2015

Here’s a snapshot of our upcoming 2015 calendar and also around the country, thanks to BLOUIN ARTINFO

At RAYGUN

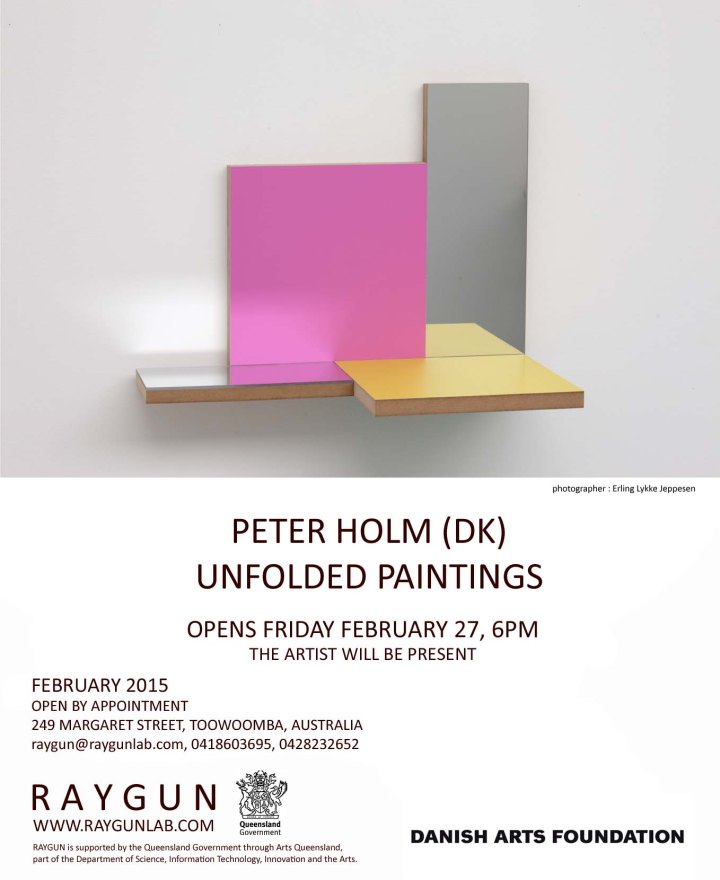

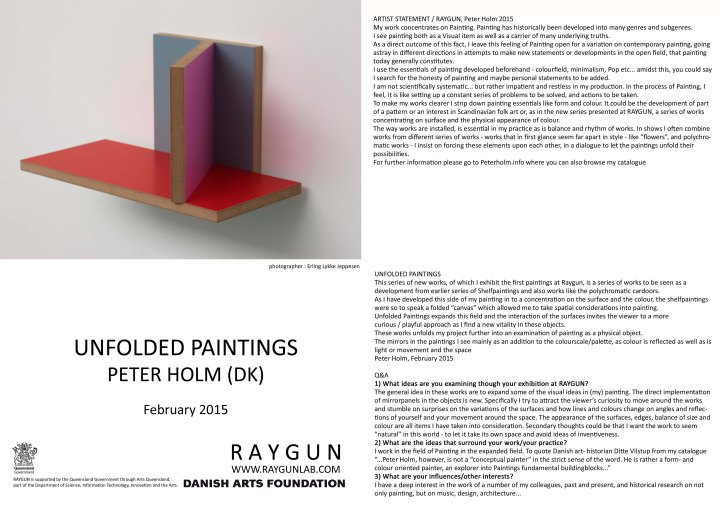

February – Peter Holm – Denmark. Visiting Toowoomba and Sydney

March – John Rubin – USA. Visiting via SKYPE

March – PaintingOnTopOfItself – MOP Projects, Sydney

April – Audra Wolowiec – USA Visiting Toowoomba (See posts for details)

May – Sal Randolph and Graham Burnett – USA Visiting Toowoomba

June – Olivier Mosset – USA

July – Exchange with West More West, Blue Mountains New South Wales – Reductive Painting

August – Jason McSweeney – Western Australia Visiting Toowoomba

September – Matthew Deleget – USA Visiting Toowoomba

October – Eva Koch – Denmark. Visiting RAYGUN Toowoomba and Dogwood Crossing Miles, Australia

November – John Rubin – Visiting via SKYPE

December – Justin Andrews – Melbourne Visiting Toowoomba

And around the country…

http://au.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/1071965/10-must-see-art-exhibitions-in-australia-in-2015

Thoughts on Painting today

A sublime piece of writing on art today, and where painting, in all its grace and presentness, holds consistently steadfast.

But to the extent that the work is ideologically potent, it loses its aesthetic compulsion, its power to hold and demand our visual attention simply by virtue of its sensible characteristics and arrangement. If the work is truly drenched in interests and ideology, then its authenticity is parasitic on our agreeing with the interests and values the work promotes. All this will drum the work itself out of sight and into reflection.

J.M Bernstein – Against Voluptuous Bodies: Art, Objecthood, and Anthropomorphism 2006.

un-bound-ed SAN FRANCISCO

Before 2014 comes to a close it’s time to update the lab with news of a few matters of interest that occurred throughout 2014

A group painting show curated by Brent Hallard in San Francisco titled un-bound-ed based on the idea of reductive painters, from one generation to the next, and how each interpret their practices through the reductive, non-objective genre. The installation included works by artists from various countries and consisted of painting on canvas, wall painting, collage, video and sculptural works. Check out the list of contributing artists, an essay by Joan Waltemath and images from the opening night.

crossing the line/undoing the eye/I: a reflection on category by Joan Waltemath

…there is no perception which is not full of memories. With the immediate and present data of our senses, we mingle a thousand details of our past experience. In most cases the memories supplant our actual perceptions, of which we then retain only a few hints, thus using them merely as “signs” that recall to us former images. The convenience and the rapidity of our perception are bought at this price; but hence also springs every kind of illusion. Matter and Memory, (1896) Henri Bergson p. 33, Zone Books, 1991

The awareness that habit diminishes perception, allowing us to draw largely on memory images to navigate while our conscious mind rests or drifts, is not second nature; it is rather a result of conscious effort and focus. Only by turning our attention to the act of seeing, like Bergson did, can we become cognizant of the ways in which the things we know affect what and how we see. In the 19th century Henri Bergson proposed that in order to see the thing that is in front of us we first sift through our memories to find something similar we know already. This tendency becomes a form of automatic categorization that allows us to contextualize our initial discernment as we sort through the myriad of phenomenon confronting us. We can begin to distinguish what we are seeing and apprehend its uniqueness when we have registered a point of reference. Bergson assumed that such various and unpredictable associations account for how different people see the same things so differently. The complexities of these dynamic, yet oppositional tendencies in perception underlie un·bound·ed, an exhibition at Root Division in San Francisco, organized by artists Brent Hallard and Don Voisine.

Hallard and Voisine found a common interest in their understanding of how cultural conditioning and modes of apprehension, whether they be genres, sub-genres, tendencies or trains of thought in works of art, can limit the range of interests that seem to be operating within and around objects of vision. Their perspective on the ways we identify contemporary art through its association with other works, similar in some aspects but wholly different in others, lead them to seek out artists for the exhibition who are using various strategies to exceed the limits of these cultural conventions as a means to catalyze perception. They sought both artists that cross the boundaries of different disciplines and modalities, as well as artists whose work necessitates a means of presentation or classification that does not always accommodate conventions. Often such work, though innovative, becomes obscured. For un·bound·ed they have brought together a diverse group of works from five different cities across the globe, as well as different generations of artists, with the belief that such work is essential to the longevity and vitality of our fine art culture. As an artist who writes about art they invited me both to participate in the exhibition and to dialogue with them in order to create this text.

Working from a point of view that is inherently visual and not rooted in theory or textual references, Hallard and Voisine let their choices be guided by formal relationships and an innate understanding of artworks that seem to speak the same language as they initiate an investigation of questions surrounding categories, conventions and the limits of genres. Grouping these works together has the potential to create a category of its own, so let me also acknowledge that the organizers did not intend to imply that the works chosen constitute an art movement, or community of any kind, or that the artists themselves necessarily considered the theme of the exhibition in producing their work. Rather they recognize the affect of the works chosen and how their relationship to each other will serve to shed light on the many artists working not only today, but for generations, in non-objective and process oriented modes that are grounded in an evolving sense of what creates a visual experience.

Since we have become richly acculturated to the disciplines of painting, sculpture and more recently film, video and installation, we can enter an exhibition or projection space and immediately view works as belonging to one of those categories without being aware of how that affects our apprehension of them. Along with these categories come a whole set of deeply embedded expectations that govern our reception of works of art, i.e. if we do not anticipate a sculpture as offering what a painting might offer, we don’t necessarily look for it. In most cases we see what we are looking for, making it a challenge to accommodate the heretofore unseen and unexpected in our view. Embedded in language itself is the root of this understanding – recognize – to become cognizant again. Every artist faces the challenge of breaking though this barrier both to get beyond the initial phase of “this looks like X ” that is an important part of looking at works of art and to make a new vision perceptible.

The unfolding of experience, like that which happens in the simple and unencumbered work of Mel Prest, for example, creates a strong counter to the perception of what appears initially to be ‘another stripe painting’. On the surface of her modestly scaled canvas’s Prest’s scribble lines and carefully painted strokes generate what in the final analysis becomes an image. When her lines wrap around the canvas’s edge it becomes a thing-in-itself, and after a few moments of focused attention one can feel her gestures breathing with their regular and irregular rhythms. Going back over the sequence of her strokes being laid down, it’s easy to get caught up unfolding the multiplicity of dimensions that her pattern creates. Then she has captured us alive, for one brief moment.

The expansion of awareness that can stimulate perception and activate our consciousness when experiencing works of art is so often so short lived. Even works that momentarily escape the conventions surrounding them soon become a reference point for other works; and hence a new convention. When they are finally referred to as such they will cease to actually be seen or discovered. The inevitable progression in the assimilation of innovation is a kind of ‘one step forward, two steps backward’ process, which takes place over generations of artists. It demands of the artist a continual reassessment of the given in order that the things being made can continue to be perceived and an awareness of how even slight shifts in context, form, genre, materials, modes of installation or other categorical limits push us to see and therefore think in new ways.

An artist who seems to be acutely aware of this problematic is Zachary Royer Scholz, whose found encounters with materials serve as a pretext for a complex engagement in the interstice of life and art. Peruse his works constructed with mattress foam or his foam mattress installation at Headlands Center for the Arts and you’ll never think about that material the same way again. Though Rachel Whiteread’s plaster casts come to mind, Scholz has wrestled away the mattress as her exclusive territory by shifting both focus and perspective. We come away thinking about the possibilities of the material, its flexibility, its color, how it ages, it’s haptic presence, as it has become more than a more or less adequate surface to sleep on or a piece of Whiteread’s vocabulary – without losing those things either.

The work of Alain Biltereyst takes an entirely different approach, although to similar effect. Biltereyst’s small painted works on plywood are constructed in such a way to recast the Painting as a Window / Painting as Object dichotomy. The small rectangular formats of his support’s surfaces have a particular exacting scale in relation to their breadth. A subtle tension between the panel’s sometimes laminated, sometimes blocked in sides and the simple geometry of their surfaces causes the character of their objectness to become primary, all the while keeping the latency of his surface in tact. Biltereyst’s illusion of depth is negligible; rather, he has reinvested it as a concrete element that interrupts a habitual pattern of engagement with a painting. While Biltereyst’s works feel inevitable in a logical way and their depth is located in the depth of the panel instead of the illusion of depth on the surface, their surfaces often still mysteriously retain echoes of the pictorial. So we necessarily reframe our expectations when apprehending a painting that presents itself as an object all the while speaking a pictorial dialect. Biltereyst’s surfaces, nuanced and worked, hold attention for a significant duration. And as they hold us they create the time to reflect and to review in response to what we are seeing.

The often imperceptible line between perception and memory Bergson speaks about plays out in Dean Smith’s contribution to the exhibition, Video mandala IV. His images cycle through a series of pulsating circular forms that work like a kind of science experiment or evolutionary morphology to both activate and mirror the retina. It’s form feels more like a painting, with reference points, like Dan Christensen coming from op and color field painting, yet the effect is altogether hypnotic in a way only media can achieve. Video mandala IV’s reflective nature lies in the potential for its cumulative affect to effect viewer, while the flickering screen keeps our rapt attention secure.

When the immediacy of our perception gives way to presumption or if in looking at things we unconsciously estimate their presence and appearance based on a thing previously seen, we cannot perceive particularity. All this happens in a split second of dismissal, “I’ve seen this before.”. Often it takes an effort of will to push beyond the limit of what we think we have already seen or experienced. “Conscious perception signifies choice and consciousness mainly consists in this practical discernment”.[1] This is the field much contemporary painting and drawing acts upon, engaging in a play to make one see the thing as it is, as if this remote possibility of pure presence were sanctity.

This appears to be what is at stake in Richard van der Aa’s pure white forms of solid wood that often sit on the floor. His precise placement of them in relationship to the surrounding architecture signals an absolute transcendence made palpable though their physical forms. It is partly his insistence on them as ‘paintings’ and not sculpture that causes us to take a second look and pushes the objectness of his painting’s support to a new limit. The means to re-engage perception by subverting the categorization of what we have become accustomed to seeing, is being used in different ways by several other artists in un·bound·ed.

Prajakti Jayavant’s painted paper works fold and bend the monochrome plane until they are neither painting or sculpture, but both. And although they hang on the wall, their protrusions engage a sculptural sensibility through a quasi-painterly form – one that is integral. Nothing is stuck on here. The resulting uniqueness of her objects makes them feel like something not seen before; oscillating between painting and sculpture, they ask us to reconsider the permeability of the border between the two disciplines in a way that articulates both a generational and cultural perspective.

Also in Kirk Stoller’s works we might first think we are looking at sculpture and gravitate to the characteristics of his forms. Their significance is being determined in how the forms strive to reach the limits of their own stability as they move away from a place of comfort towards unpredictability. However, the formal language Stoller has developed marries color to form in a way that makes them both equals and inseparable. Traditionally in polychrome sculptures the color is subverted and essentially becomes a surface decoration that helps to distinguish form. Yet Stoller’s color relationships have been calibrated with a precision that determines the aura of his pieces and, whether his surfaces are found or painted fresh by the artist, color takes on a primary role. We begin to question whether we are looking at wacky supports for abstract paintings or sculptures that have been painted. There is no resolution: the tension obtains. Their haptic presence opens them up to be variously interpreted in a way that transcends the boundaries set by form and color, and the limits of painting and sculpture. When they no longer represent something but are something the pure presence of their materiality forces us to see them as things-in-themselves. Thus subverting conventional categorization, Kirk Stoller too, takes a shot at making us look at his pieces for what they are – standing in front of us, teetering on more than one edge.

Linda Francis’s approach to disciplinary transgression is also one of her own making. Initially Francis paints her 2 panel canvases’ surfaces, quickly and without specific inflection so as to leave clear evidence of her brush marks. Her patterned black and white images are silkscreened on top of this prepared surface. Consequently her multidisciplinary process raises the questions: Is this a print or a painting? a hybrid or a singularly complex process? Images of her work do not convey how scale changes between the two panels affect the pattern, making the sameness of the image appear to be something other. One has to be present with her works to perceive their subtle offering and experience the double take that occurs when realizing the two images are in fact the same one at different scales.

The notion of multi-modal perception comes to mind when Gilbert Hsiao speaks of the “aural dimension of painting”. His colored lp’s spun out on turntables to dazzling affect with black light move between 2 and 3 dimensions and between the visual and the aural when he performs with them to “9 Beet Stretch” by Leif Inge (Beethoven’s Ninth stretched out to 24 hours). While Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs initially set up the class of objects crafted to make a design take on dimension through rotation, Hsiao updates it with light effect, dj performance style and more volume. Whether combining sensory modalities, splicing up styles or mixing up genres, like in Kyle Jenkin’s video laden with dime store wisdom, Monochrome Cowboy, it is the reframing of terms occurring in the mix that initiates a new form of apprehension.

The group of artists assembled by Hallard and Voisine, from San Francisco: Brent Hallard, Prajakti Jayavant, Mel Prest, Zachary Royer Scholz, Dean Smith and Kirk Stoller; from New York: N. Dash, Linda Francis, Gilbert Hsiao, Bret Slater, Don Voisine, and Joan Waltemath; from Paris: Richard van der Aa; from Berlin: Anette Haas and Tim Stapel; from the Australian collective REFLEX Projects: Kyle Jenkins and Tarn McLean and Belgian artist Alain Biltereyst presents an enduring tradition of formal based works that often play on the languages of their respective disciplines, languages which have evolved in significant ways since the Modernist period when many of the styles recognizable in this exhibition were initially seen and contested or the groundwork for their conceptual parameters established.

The tradition of abstraction and non-objective work that dominates the exhibition proposes both a recognition and subversion of the artistic vocabularies that were initiated during the period of the avant guard, when the impetus was to clear the slate, destroy the old and root originality on the tabula rasa. Today we find ourselves in radically different terrain: the syntax and vocabulary that develops in the visual languages of much of the work presented here relies on scores of artists, both past and present as well as future to be wholly understood. Insider codes abound. Hallard and Voisine gravitated to works they found authentic, where one can hear each artist’s unique voice. This understanding of the need to acknowledge and build on works within a specific lineage while using their vocabularies to articulate an individual position offers a model for understanding notions of authenticity and newness. Hallard and Voisine have highlighted its ability to engender perceptual experiences.

While each of the individual artists necessarily approaches the subject in their own fashion, what all these works naturally assume is that what lies in the object or work itself bears scrutiny, that, in fact, something to be discovered lies there and not solely in referents, analysis and association outside the work. While this position is often labeled as formalism, with the presumption that merely formal decisions comprise the work and that issues and content are excluded, the complexities of the work presented here make clear that it is not all that simple: rather formal language is being used as a means to convey content.

The recognition that visual language evolves and deepens in dialogue with other works is an acknowledgement that something is being communicated. Language does not spring up to no accord. The clarity and intensity of the transmission is fragile and dependent on the perceivers, both their knowledge and their willingness to receive; meaning develops in communication. The boundaries are permeable on all sides.

[1] Matter and Memory, Henri Bergson, Zone Books, 1991, p. 49

HAPPY CHRISTMAS and THANK YOU

Happy Christmas and New Year to all of our RAYGUN supporters, artists and followers.

Thank you for spending the time with us again in 2014 and helping to make our RAYGUN journey as awesome as it’s been. To all of our artists who have worked with us to make our calendar so special and dynamic, to our audience, both in Toowoomba and in other locations around the world, and also to our online followers. We especially would like to thank Arts Queensland for their ongoing support in believing in what we do and allowing us to to connect international artists with members of our local and regional community.

Have a safe and happy season and we can’t wait to share 2015 with you for another dynamic year in the Social Arts and Painting Expanded.

Ali and Tarn xx

Anna McMahon ‘The world is weary of me, and I am weary of it’

Sydney based artist Anna Mcmahon’s exhibition opened in December. Anna installed the works in relation to the RAYGUN project space. The ephemeral plant based works will go through their natural dying/decaying process throughout the duration of the works installation. The works, in addition to responding to the physicality of the space, were autobiographical. Below are Anna’s statement and answers to the questions we ask out artists.

Artist Statement

In The world is weary of me, and I am weary of it, I go about my arrangements with the intention of creating something that is reflective and inspired by traditional and non-traditional Ikebana displays, but without restraint about what may or may not necessarily be traditionally accepted. In his seminar from March 16, 1977, Roland Barthes describes his dossier on flowers. One of the main points Barthes makes is that flowers ‘go without saying’, that they are accepted for what they are without question of what they represent. It is for this understanding that Barthes expresses the need for a dossier of enquiry – that things that are easily accepted are often the things which ask to be looked at closely. No one questions the presence of flowers, the gift of flowers, the consolation of flowers – their presence is never thought odd, or unreasonable. They have no use, no set symbol, yet represent many ideas and ideals which contemporary society seeks to enable.

By using photography and living sculptures in The world is weary of me, and I am weary of it, the installations ultimately explore ideas of permanence and impermanence, life and death, and relevance and irrelevance.

Questions:

1 – What ideas are you examining through your exhibition at RAYGUN?

Created to attest to the luxury of the plant, a flower bears no real purpose other than to attract the insect that will aid in its reproduction. An arrangement of flowers is an impermanent sculpture – a dragged out performance of the beautiful and the ugly. As an object, and for the audience, the floral arrangement is firstly a reminder of the love and comfort of life – the simple pleasures. They recall a celebration of love and of life. However, conversely it also brings about memories of death and illness, of our own mortality and decay – that inevitable known – that life leads to death. In my exhibition, The world is weary of me, and I am weary of it, I install a number of arrangements of flowers as response to my recent travel to New York City. I approached all of my installations as an intuitive experience, wanting to create something that is both visually and physically engaging. Once the flowers are installed in the space I photograph the arrangements and having printed them, hang the image in close relation to the arrangement. The relationship that exists between the arrangement and the image is of great important to the overall work, and established the tension between the photograph and it’s index. The photograph announces the death of a moment. The light that touches the subject also writes the image, and the image becomes a precursor for the future – a description of what has been. In this way the photographic image in this work was the antithesis of death, it allowed the subject to live on through the photographic image, whilst the subject itself slowly decayed over the duration of the exhibition. Paramount to the work was the dichotomy of the ideas about death and life, preservation and decay, celebration and mundane, performance and stillness, usefulness and lacking purpose. Further to this I am also interested in how the arrangement itself may more easily constitute art when it is staged alongside its own image.

2 – What are the ideas that surround your work/your practice?

The idea of the dilettante is something which is of great interest to my practice presently. A dilettante is someone who studies a subject or area of knowledge superficially. My work resonates with this idea of the dilettante as I create floral arrangements based on an amateur study of Ikebana. In Brian Eno’s interview recorded for the album From Brussels with Love,[1] Eno states, “For me the great strength of dilettantism is that it tends to come in from another angle […] an intelligent dilettante will not be constrained by the limitations of what’s normally considered possible; he won’t be frightened, he’s got nothing to lose.’[2] It could be suggested that approaching a highly developed art form such as Ikebana with limited knowledge or skillset could be a way to overcome the constraints of that practice and bring with it a new conception of what the practice, and result means. The use of flowers throughout art history has been more or less confined to the field of painting. With the exception of contemporary artists such as Camille Henrot and Jeff Koons, the act of displaying a floral arrangement as sculpture, or performance has not been widely employed. Of course the rich tradition and history of the practice of Ikebana could very much be considered an artform in it’s own right. Pursuing my arrangements with the intention of not adhering to any pre-existing tradition means that I can act as a far more liberated practitioner, and indeed bring this traditional practice into the new light of contemporary art.

3 – What are your influences/other interests?

My practice is grounded in scientific, theoretical and new age notions of the past and future. I explore this area through photo-sculptural conjunctions, generally taking the form of an installation.

Since 2011 I have intermittently seen and recorded readings with multiple psychics. I am in the process of creating a body of work that presents the answers I have been given when questioning my future career as an artist during these readings. At their core these works explore fear of failure and conversely a quest for success.

Bibliography

Eno, Brian. “An Interview with Brian Eno.” By Phill Niblock. From Brussels With Love (1890).

Fox, Dan. “Known Unknowns.” Frieze, no. 161 (March 2014).

[1] Dan Fox, “Known Unknowns,” Frieze, no. 161 (March 2014); ibid.

[2] Brian Eno, interview by Phill Niblock1890.

Victor Frankl speaking about the poser if idealism and mans continual search for meaning.